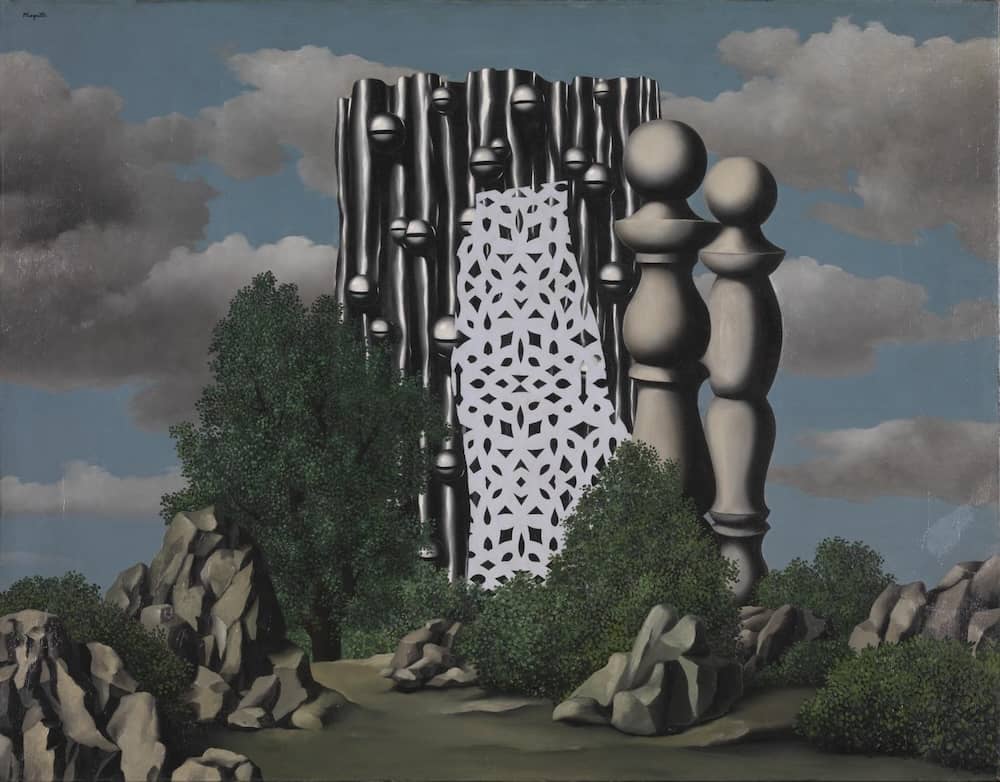

The Annunciation, 1930 by Rene Magritte

The Annunciation brings together many of the themes, both iconographic and philosophical, that engaged Magritte during his stay in Paris from 1927 to 1930, a period in which he was closely associated with the French Surrealists. The painting shows an unlikely combination of objects. Two large bilboquets (Magritte's term for the objects in his works, which, though imaginary, recall wooden balustrades or chess-pieces) stand next to an oddly shaped piece of paper with a decorative cut-out pattern. Behind them looms a grey metal 'curtain', hung with sleigh bells. Despite its incongruity, this collection of objects seems disconcertingly 'at home' in the rock-strewn landscape beneath the grey clouds in the blue sky. The size of the painting (it is one of the largest the artist ever executed), together with its traditional composition and subtle allusions to paintings of Old Master like Leonardo da Vinci, Titian, and Caravaggio, are signs of the ambitiousness of the work.

Annunciation, the title given to the painting by the time of its first public showing in March 1931, seems unrelated to the subject matter of the painting. However, its religious connotations seem strangely appropriate to the work's serious mood: there is no Mary, or Archangel, yet the strange stillness of the imagery suggests that something momentous either has just happened or is about to, and that what we see is, in fact, some sort of vision (in his letter to Mesens, Magritte described the central grouping of objects as an 'apparition'). Sylvester (1992, p.187) writes, 'There are numerous instances of the sublime in Magritte's art, but nothing else as numinous as this ... "The Annunciation" impresses through its majesty, its solemnity, its luminosity, its silence'.

Magritte himself was not a believer, and would have thought of the mystery implied in the idea of 'annunciation' in a purely secular sense. An uncritical use of a term so central to Catholicism, however, would have been anathema to the Surrealist group, and it is likely that the title was intended to be not only ironic but also provocative. Magritte had quarrelled with the leader of the French Surrealists, André Breton, on a matter relating to religion in December 1929, and the rift between the two men was to last until 1933. At a gathering at his home, Breton, who, like all the Surrealist writers, was an arch-atheist and anti-cleric, noticed that Georgette was wearing a cross, and asked her to take off 'that object'. Georgette habitually wore the cross, which had belonged to her grandmother, and preferred to leave with her husband rather than remove it. Magritte was deeply angered and upset by this seemingly rather trivial incident, and rejected attempts by friends to effect a reconciliation. Yet the fault was not all on one side: many present at the incident felt that Magritte's hostile response was not entirely justified, particularly as it seems that he had long attempted to provoke Breton on the subject of religion.