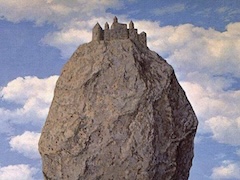

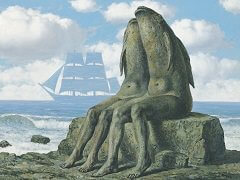

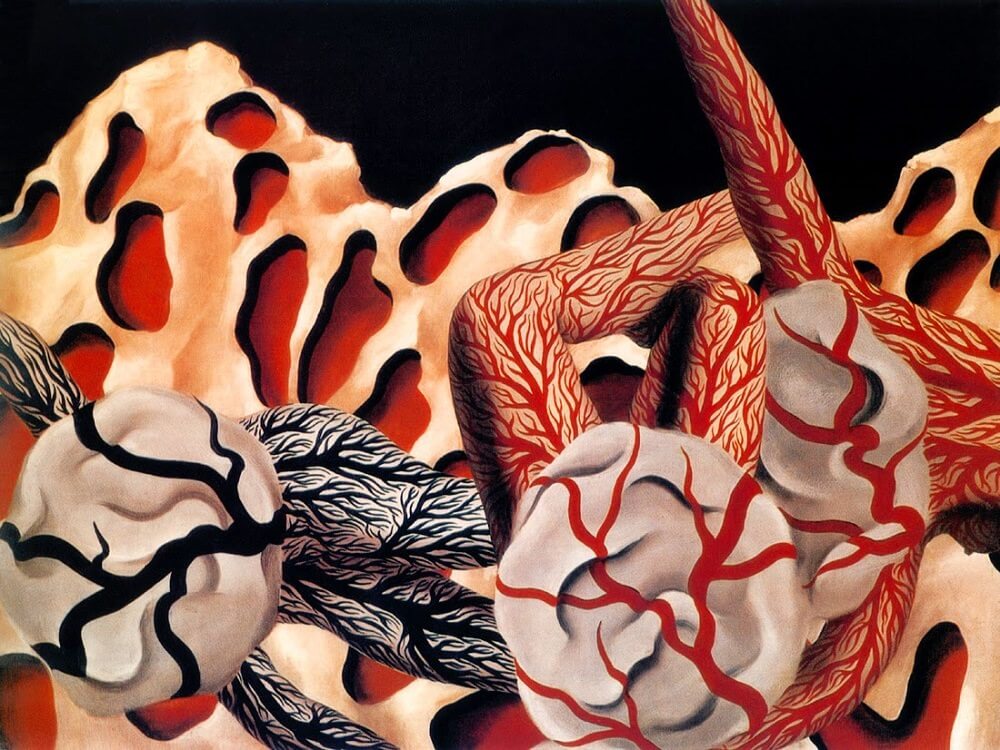

The Blood of the World, 1925 by Rene Magritte

From 1925 on Magritte took two paths, one of which he was still following about 1930. The Blood of the World belongs to a group which he abandoned after 1930 and which is clearly

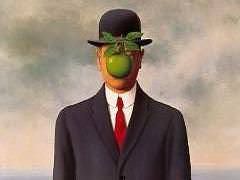

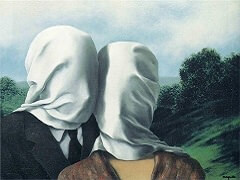

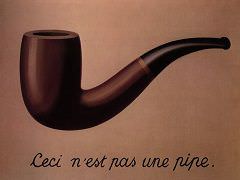

distinct from the works based on recognizable figures, belonging to a world of people and objects brought into strange relationships with one another and placed in unexpected settings, as

exemplified by The Lost Jockey, a theme which Magritte took up again and again.

The other direction, which emerged shortly after the motif of The Lost Jockey, consisted of invented organisms, vegetation, and forms only indirectly and ambiguously related to

reality. Only through associations can one approach these oppressive landscapes; visually tangible and clear, they are peopled by forms that are intertwined in the Baroque manner.

The Blood of the World shows organisms resembling legs and arms which lack their extremities and have been skinned, like those in pictures of anatomical lessons. The round forms which

they partly cover are even more difficult to approach. The art historian could venture a reference to Arp's forms in his Dada period, or one may be reminded of

Max Ernst. Magritte, who made these paintings shortly before or during his years in Paris, from 1927 to 1930, saw many things in Andre Breton's circle

there, but this fact does not lead us in the right direction. The forms immediately behind the so-called flayed legs, for instance, may seem like certain phases in rock formation, with signs

of erosion. Antoni Gaudf, the Spanish Art Nouveau architect, fashioned similar "growths," and Dali was always fascinated by them on the shore of

Cadaques, near his birthplace. Magritte gives them artificial colors here - bloodred and off-white.

In The Blood of the World one can discern the demon in Magritte's imagination, the obsession with a dark fertility urge which has a perverse side to it; it was a remnant of

Expressionism, from which he freed himself about 1930. Then came the clarification, the mysterious clarity, of which he was a master as early as 1926.